Understanding The Language in Biology: Protein Sequence Embeddings

In natural language processing (NLP), in order for computers to understand human language, unstructured text are converted to vetorized representation known as “word embeddings”. Many well-established methods exist for this purpose, such as Word2Vec and Doc2Vec.

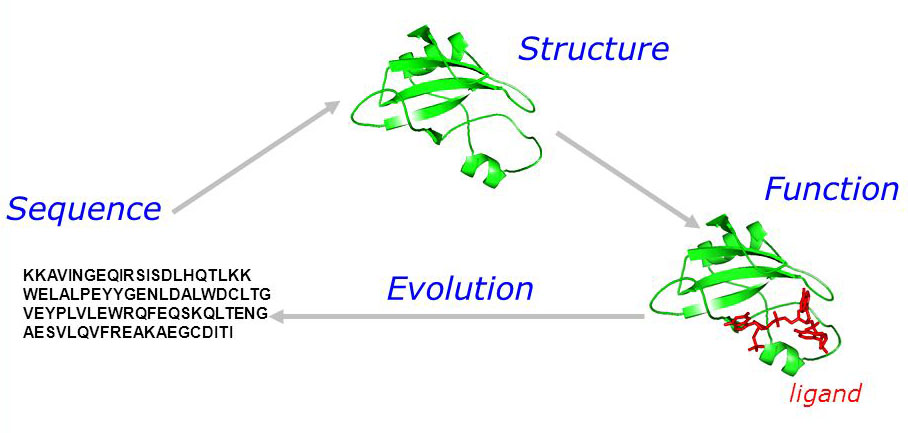

Protein sequence are a very important language in nature, each sequence is a unique combination of 20 amino acids arranged in a specific order that results in a unique physical structure which correponds to a unique biological function. Understanding this language can help us predict diseases, design new drugs, and even achieve immortality!

Fig 1. Protein sequence-structure-function relationship.

However it is extremely hard to understand this biological language, because the sequence-structure-function relationship is very complex and not at all straightforward, which makes it one of the “holy grails” in biology.

In the recent years, the application of machine learning and NLP techniques in the study of proteins has attracted a lot of attention. In these studies, “word embeddings” of protein sequences were applied in order to address the unstructuredness of these sequences. There are many methods that have been developed now, and I want to introduce a few of them here.

One-hot encoding

The simplist embedding system in NLP is one-hot encoding. It could also be applied in protein sequence. For example, If I want to encode the protein sequence GHGLY, then I can encode each position with 19 zeros and one 1. As simple as it seems, one-hot encoding can actually achieve a lot. In certain tasks such as sequence clustering or protein classification, one-hot encoding can be quickly implemented and provide a lot of insights!

Fig 2. One-hot encoding for protein sequence.

One-hot encoding is usually a good default in practice, but it has a few drawbacks, especially in biology. First, it is a sparse representation and occupies a lot of memory space. Think about the zeros generated for a 200-residue long sequence! Secondly, it does not reflect the “biological meanings” of these words. Different amino acids are different chemical compounds, and they has different 3-D strucures and chemical properties, and those properties are what makes one sequence different from another, but they are not captured in one-hot encodings. Thirdly, one-hot encodings do not consider the interdependence of the amino acids in terms of their relative positions. The context of a amino acid in a sequence are often determining how this amino acid behaves in structure, and one-hot encodings fail to encode this information.

Property-based embedding

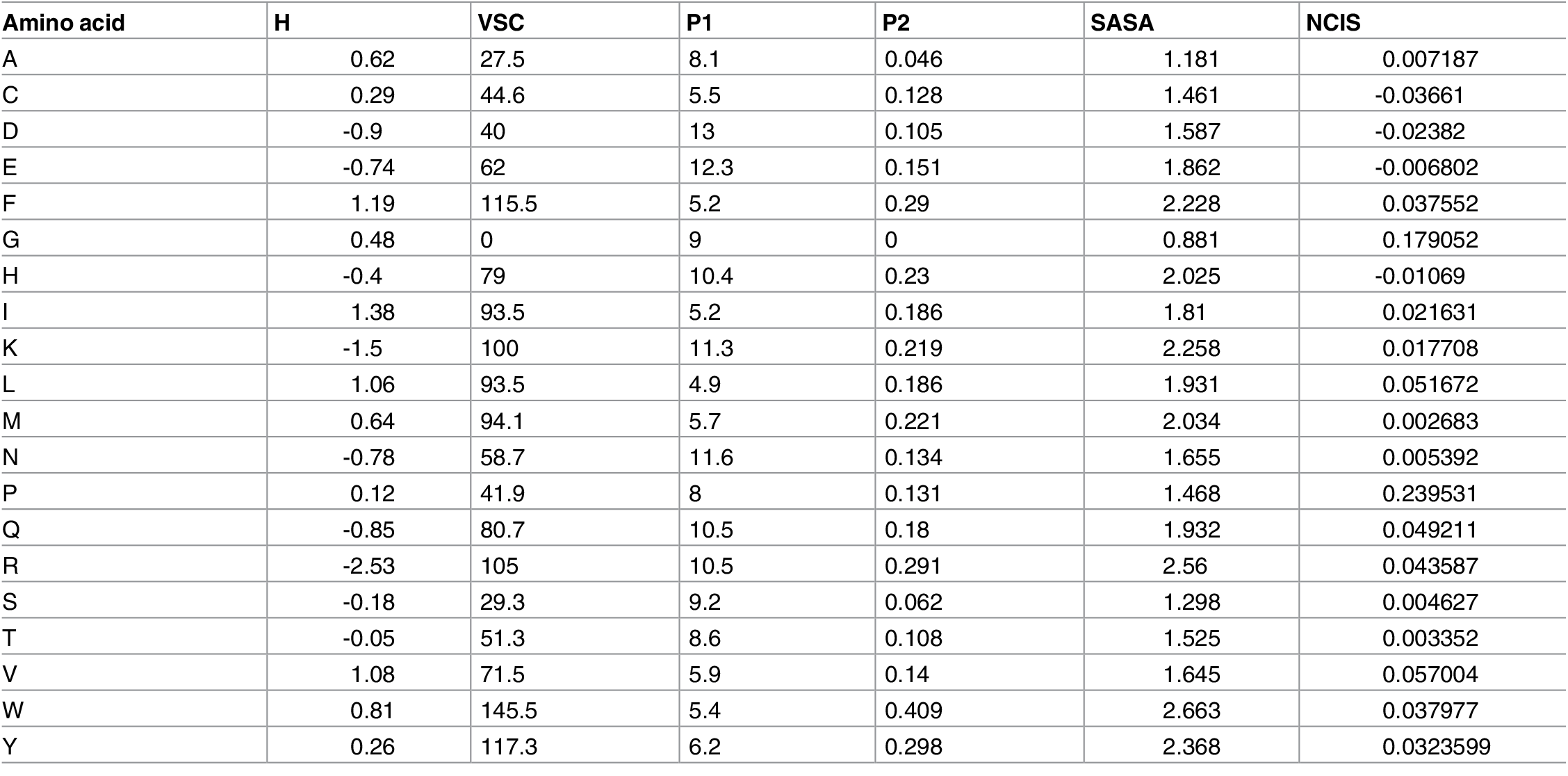

The property-based embedding is based on the assumption that a protein’s biological function is primarily determined by the physicochemical charasteristics of amino acids in its sequence. These charasteristics includes hydrophobicity, polarity, charge, secondary structure, and so on. A pre-calculated multidimensional vector for each amino acid is applied to the entire sequence, therefore one sequence is represented by a matrix.

Fig 3. Different physicochemical properties for 20 amino acid types - Hydrophobicity (H), volumes of side chains of amino acids (VSC), polarity (P1), polarizability (P2), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) and net charge index of side chains (NCISC).

Property-based embedding is very commonly used in the prediction of protein-protein interactions, mainly because those interactions are mainly driven by these encoded physicochemical properties. It is also used in protein classification tasks, because different protein functions may require different chemical properties. For example, keratin in our hair is very hydrophobic!

However, the problem with property-based embedding is two-fold. First, these manually picked physicochemical properties are just a subset of what the sequence really entails, and we are missing the other parts, which sometimes may be very important. Secondly, again we are missing the context information of each amino acid in the sequence, which makes property-based embedding not suitable for a number of structure-related tasks, because protein structures are highly dependent on the sequence context info!

Context-based embedding

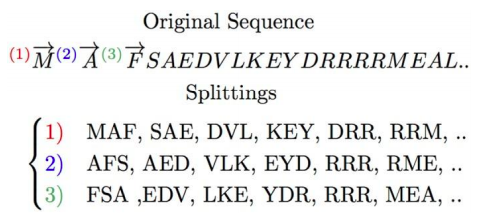

In Word2Vec, a distributed representation of words was trained with hierarchical softmax and negative sampling in a neural network. It essentially “learns” the relationship between words by remembering similar words that occurs in similar context. This method can also be applied in protein sequences, but there is a small problem: what are the “words” in a protein sequence? Biologists often divide sequences into different parts (“domains”) based on their knowledge about this sequence’s structure/function, but computers have no idea. Therefore, a common way to break sequences in context-based embedding is to use the n-gram model.

Fig 4. Breaking a protein sequence into 3-grams.

Context-based embedding turned out to be very successful in many tasks, especially structure classification. It can tell proteins with confined structures apart from IDPs (intrinsically disordered proteins). IDPs is a very special class of proteins that we know very little about. It doesn’t fold into a stable structure yet play very important roles in biology. IDPs are quite diverse in sequence, yet can be fairly represented using context-based embedding.

Fig 5. Classification of folded proteins versus IDPs using context-based embedding.

Context-based embedding is the current focus of many computational biologists (including me!) working on protein structure or function prediction. It is very powerful in these tasks and beyond, largely because context-based embedding is generally trained on massive datasets of proteins (there are 150,000,000+ sequences in uniprot), and therefore provides a lot of hidden information about a sequence! However, the downside of context-based embedding is interpretability. The datasets that it trains on are usually unlabeled, which means that we don’t really know why one “word” is next to another in the sequence, we just know that the statistics says so. A lot of efforts by scientist are being done in order to address this issue, and I will continue to introduce some of them (incluing my postdoc work) in the future.

References:

[1] https://medium.com/proteinqure/welcome-into-the-fold-bbd3f3b19fdd

[2] https://deepmind.com/blog/article/AlphaFold-Using-AI-for-scientific-discovery

[3] https://dmnfarrell.github.io/bioinformatics/mhclearning

[4] Zhou C, Yu H, Ding Y, Guo F, Gong XJ. Multi-scale encoding of amino acid sequences for predicting protein interactions using gradient boosting decision tree. PloS one. 2017;12(8).

[5] Asgari E, Mofrad MR. Continuous distributed representation of biological sequences for deep proteomics and genomics. PloS one. 2015;10(11).